Note from AFSP’s Director of Writing and Entertainment Outreach, Brett Wean:

Aside from being a suicide prevention advocate, I happen to be a huge comics (and horror) fan — and know from personal experience how impactful stories involving mental health can be on an audience. Whether it’s TV or film, in a podcast, or a comic book, the way creators handle this complex topic can encourage help-seeking, provide authentic examples of how to talk about mental health with someone you care about, and raise our culture’s understanding. Of course, we also know from research that if handled badly, stories can run the risk of having a harmful effect.

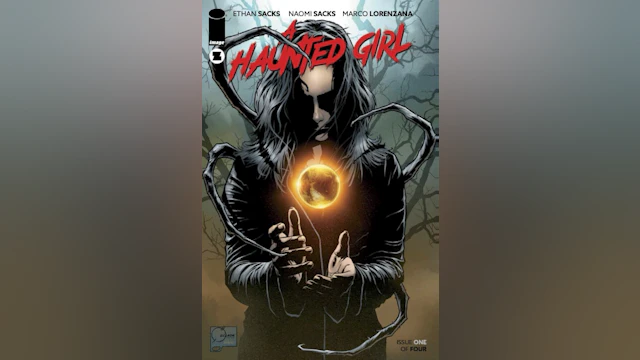

A Haunted Girl is a four-issue graphic novel horror miniseries written by acclaimed comics writer Ethan Sacks, alongside his daughter Naomi. While the “external” plot is scary and supernatural, the main character’s inner journey deeply involves mental health, as she returns to high school after a stay in a psychiatric hospital.

Ethan and Naomi reached out in advance to AFSP to make sure they handled the topic safely, and it was my pleasure to work with them on this fun and creative project — including providing a page of resources to be included in each issue, ensuring that more people will find out about the support that’s available to them.

What was the inspiration for your new graphic horror miniseries A Haunted Girl — particularly the inner journey of the main character?

ETHAN: I jotted down the original idea for A Haunted Girl in a notepad four and a half years ago — while I was waiting in a hospital cafeteria between visiting hours in the pediatric psychiatric ward upstairs. My daughter, Naomi, was hospitalized with severe depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, and all of a sudden our family’s world completely changed. Feeling overwhelmed and more than a little guilty that I had “failed” as a parent in missing all sorts of warning signs, I felt powerless in the moment. But as a professional comic book writer for Marvel, I wondered: what if I could come up with a story that would be inspirational to my daughter and other teens and twenty-somethings going through similar struggles?

I looped in a creative partner, artist Marco Lorenzana, and we started working on a story. Naomi is now in a place where she could lend an authentic voice to Cleo, our protagonist, and all she is experiencing. Scenes in the comic involving therapy sessions, hospital routines, and school refusal sequences all came from a place of personal experience.

The result is A Haunted Girl, a four-issue comic book series that debuts on October 11th at comic stores everywhere, and which will ultimately be collected in a trade paperback format for bookstores next year. It’s about a girl who is struggling with depression, who suddenly finds that she is the only person who can save everyone else from a supernatural apocalypse.

Have you ever written any together before? What is that process like? And what is it like to work together as father and daughter?

ETHAN: Not exactly. When Naomi was younger and I was a journalist at the New York Daily News, she did write several articles as a kid reporter. But I largely gave edits and advice. This time around the process was complicated a bit by her going away to college. So, we started by coming up with a very detailed outline — breaking down all four issues scene by scene — while she was back home during the winter holiday break.

NAOMI: When I went back to school, we used a shared Google doc to work from and left comments for each other. There were Zoom calls, too. It felt like we had our own areas in which we were working. Obviously, we shared our opinions on each other's work.

Naomi, for you in particular: what is it like, based on your personal experience, to examine the character of Cleo? You’re further out from your experience, and in a healthier place, managing your mental health. But Cleo, in the story, has just been hospitalized as a result of her psychological crisis. How does your present-day perspective apply to your work with the character? If you could talk to her, is there anything you want to tell her?

NAOMI: A lot of it was saying things that I never got the chance to say or fully knew at the time how to articulate. So in that way, the dialogue is not taken out of thin air. It’s often things that I wanted to have said. In order to do that, I needed to go back and tap into these emotions that were maybe buried or dusty. When I channeled those feelings to write, they came back – maybe not full force, but still pretty strong. It knocked the wind out of me sometimes. It could be exhausting because of how intense those feelings were, even if it’s just a memory.

There is a bit of a catharsis in that. Being able to say things that I felt were unsaid. Sentiments that I wasn’t able to fully voice yet. I did feel a bit lighter overall by the end of the writing.

As for what I would tell Cleo: The expected answer would be something like, “It’s going to be okay, you’re doing great.” That’s something I heard a lot. Even if it’s something I now know to be true coming out on the other side, at the time it didn’t really register. So, I guess I would want to just give her a hug. And listen to her. And have her know she’s listened to and cared for.

Ethan, you have a different standpoint here, as Naomi’s father. What elements did you want to explore in the story, based on your experience caring for Naomi and trying to be there for her as a parent?

Ethan: What was most important to me is that readers get a sense of how strong Cleo is to keep persevering — even when she feels she is at her weakest. And also, that she had friends and family and mental health caregivers there to help share the load. She was never alone, even when she felt most isolated. That was our experience on both fronts. It was also important to convey that parents can often unintentionally inflict damage by what they say, even if it’s meant out of love. “It’s not a big deal,” as an example. That may be an attempt to make your kid feel better, but it also can feel to them like you’re minimizing their pain and that you don’t understand. It sure feels like a big deal to them.

On a macro level, I wanted to do this as a supernatural horror story for two reasons: To be cathartic, we had to convey the scariness of what it’s like to go through this, for parent and kid alike. However, we didn’t want to be triggering, so by having a fantastical premise, I thought it could serve as a crucial buffer.

You wanted to be safe about what messages your story sends in terms of mental health, and that it be safe for readers who may be in a vulnerable state themselves. You reached out to AFSP, and had earlier gotten feedback from some psychologists. Some of the elements we discussed together were: the depiction of mental health professionals and psychiatric facilities; the kinds of conversations your characters have, including some that show people messing up or being unkind — but also some that show how a caring and effective conversation might go; avoiding a focus on lethal means related to a physical suicide attempt or death; making clear in the story that Cleo is facing an actual monster/demon and not simply hallucinating; and being authentic and real while still ultimately sending a hopeful message that help is available and that no one has to face things on their own. (I’m probably forgetting some!) How did being aware of those elements affect your process as a storyteller?

NAOMI: For the therapy scenes, having Marcy (the therapist) be a compassionate character was really important to me. Having her be a rock, and a source of warmth and stability. Therapists are really important; I’m glad to have found mine. It’s nice that Cleo gets to have that experience, too.

The depiction of mental health care workers in stories is often the doctor’s coat, the notepad, looking over the rims of their glasses and asking, “How did that make you feel?” in a cold voice. There’s nothing wrong with that kind of therapist, but that image might be intimidating to people if it’s the only representation they see. It was important for Marcy to break the stereotype of the cold, stony, unapproachable psychologist. I wanted her to be fun and goofy — while still imparting wisdom and doing her job. The warmth of Marcy’s character was very important to me.

ETHAN: We don’t know who’s reading the story, and what state of mind they might be in at the time, or where they are in their own mental health journey. A Haunted Girl needed to feel cathartic and inspiring, but not triggering. To me, by paying attention to these important details, the hope was that we would deliver a story that will let readers feel seen, feel empowered, feel inspired. Getting therapy, getting care is such an important part of getting better. We wanted to dispel the stigma that is often associated with mental health in many movies, television series, books, and comics.

Finally, how do you both feel now that the story is going out into the world? What emotions does it stir? And do you think you might work together again?

NAOMI: Honestly, I’m a little terrified. There’s the fear: What if everyone hates it? Even if I know that’s not realistic. I guess the personal nature of it also makes it scary, too. Cleo’s experience is very similar to mine. I hope other people can relate to her as well as I do.

ETHAN: Anxious. The measure of success for us goes beyond breaking even on the money invested in all the variant covers and art. It’s not about sales or positive reviews or even the potential for it to be optioned as a movie. It’s getting the book in the hands of people whose lives could be made better by reading the story. (Shout out to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention for providing us with a resource guide for the back of the book.) And that’s a challenge because there are so many comics out there and it’s always hard to cut through the cacophony of pop culture options for attention.

If you’re inspired by what we’re trying to do and thinking of buying your own copy, it helps to call your local comic store (which you can find here: https://www.comicshoplocator.com/) and order it in advance before September 18th. That’s the date of “Final Order Cutoff,” when the stores have to decide how many copies to order. Which in turn helps the publisher decide how many copies to print. Then telling others about it is appreciated, too. It all helps spread this message.

Hopefully we made an entertaining (if occasionally intense) story that provides a little boost to some readers on their own real-life heroic journeys.

Issue #1 of A Haunted Girl will be available in stores and digitally on Wednesday, October 11. For more information, click here and here.