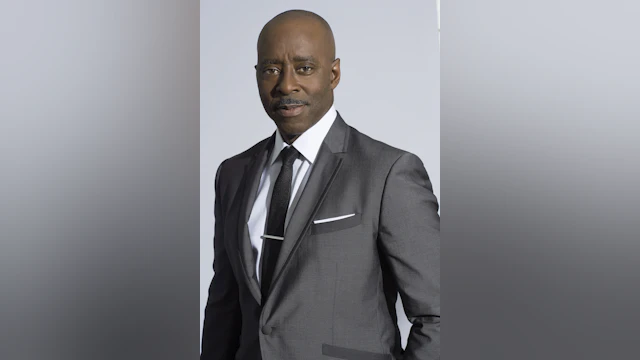

This past November, actor Courtney B. Vance and psychologist Dr. Robin L. Smith released a powerful new book, The Invisible Ache: Black Men Identifying Their Pain and Reclaiming Their Power. Below, you can read a brief introduction to this important work by AFSP Chief Medical Officer Dr. Christine Yu Moutier, followed by an excerpt directly from the book itself:

In the new book The Invisible Ache: Black Men Identifying Their Pain and Reclaiming Their Power by Courtney B. Vance and Dr. Robin L. Smith, famed actor Courtney B. Vance shares his heartfelt, personal journey in the wake of his father’s death by suicide. Prompted by another recent tragedy over the course of the pandemic — the suicide death of his 23-year-old godson — Vance has become a vocal advocate for mental health, speaking openly about the role professional therapy has played, first in his own healing after the death of his father, and as an ongoing part of his life.

It was for this reason that the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention honored Courtney at our 2022 Lifesavers Gala, acknowledging his mission to spread awareness that mental health is something we all experience and must manage, free from shame; that suicide is preventable; and that help is always available for those who need it. The book, framed with thoughts by trusted, long-time psychologist Dr. Robin L. Smith, uses this story of both loss and healing as a valuable opportunity to explore the intricate relationship between Black men and mental health in our society’s culture. It is a deeply necessary conversation and one that AFSP continues to both encourage and engage in as we expand our suicide prevention programming to include the Black Church as well as the broader Black and African American community.

We are thrilled to share the following excerpt from The Invisible Ache in AFSP’s Real Stories blog.

— Dr. Christine Yu Moutier, Chief Medical Officer, The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention

The following is excerpted from The Invisible Ache: Black Men Identifying Their Pain and Reclaiming Their Power by Courtney B. Vance and Dr. Robin L. Smith. Copyright © 2023 by Courtney B. Vance and Dr. Robin L. Smith. Reprinted with permission of Balance Publishing, an imprint of Hachette Book Group. All rights reserved.

After my father killed himself, my mother’s decision to stay put gave me a lesson in how to keep going. My sister Cecilie and I began talking about where Mom could move because we thought there was no way she could stay in the house on Appoline Street. There would be too many bad memories.

How could she ever go into that TV room again and not think of my father? Dad had filled that house with his vibrancy when he was alive, and his absence in death left nothing but questions and shadows. No. Mommy couldn’t stay there, we decided. Maybe we could find her a condo in a nice neighborhood just outside Detroit. But when we talked to our mother about leaving, she said she wouldn’t go.

“I’m staying in this house,” she said defiantly. “I’m going to work out with my Lord whatever needs to be worked out.”

My mother taught me so much in my life. She brought home books from her job at the library when I was just a toddler to teach me how to read. She helped me recognize the call of a cardinal and how it differed from the chirp of a blackbird. And she taught me that you could lean on the Lord, and a therapist too. But her choice to stay in our family home taught Cecilie and me something else. Just as she was being a role model, encouraging us to follow in her footsteps and get counseling, she was also teaching us that life is about rebounding. Life is about pivoting. Just like in a football game, or on the basketball court, when you fall, you have to get up. And if you can’t stand on your own, lean on whoever you need to until you can.

Therapy gave our family a place to take our grief, so it didn’t just consume all of the space in the house on Appoline, at my sister’s home in Germany, or inside my tiny apartment back in New York. We could talk about our sadness, so it didn’t feel quite so heavy. We had a space to ponder why Dad did what he did, why we didn’t see it coming, and even if we had, whether there was anything we could have done.

I think each of us had our own set of questions. Maybe, I thought, if I wasn’t away from home so much, from the time I was young, Dad would have hesitated, given me a call, and changed his mind. I’m sure my mother, aware of her husband’s painful childhood, wondered if she could have pushed and probed a little more.

And then there was my sister, who’d had her own very public mental health battle ever since high school. She was the one among us who’d actually been going to counseling for years. She took medication daily to steady her mood. And, I learned after my father’s death, she, too, had contemplated suicide.

My parents, knowing her dark thoughts, worked with Cecilie’s therapist to give her reasons to stay.

“Stay here for your mother,” they told her. “Stay here for your brother. But please. Just stay.”

So, for Cecilie, it was even more jarring to realize Dad had done what he’d fought so hard to keep her from doing. Now, if those terrible thoughts ever returned, she had an even bigger incentive to ward them off.

She had to be here, not only to see how her life played out, but for Mom and for me. After all, we had endured the pain of Dad’s suicide. How could we possibly survive another?

---

I also understood that, to deal with loss, there are certain things you have to let go. Like judging the person who’s gone, or yourself for not doing something different when they were here.

When you judge, you become angry. What you judge, you can’t explore, examine, or learn from. You cast blame or feel superior. You carry that negative energy like a bag of boulders on your back, and it weighs down your entire existence. I think that’s why my grandfather and uncles made sure to tell me not to judge my father when we all gathered at his funeral. They didn’t want me to carry that resentment. My therapist, Dr. K, said the same thing. To carry on with the unending grief he must have felt for his own mother took resilience. It took courage. But in the end, he just couldn’t overcome the loss of a parent he’d never known.

However, when our loved ones leave, when death does come calling, we can all remind each other that there will be a time when the memories of how they lived is more resonant than when — or how — they died.

One day, a few years back, I was speaking to a dear family friend, Miss Anita. She told me that her brother had called that morning and mentioned that it was the fifteenth anniversary of their father’s death. But Miss Anita had forgotten. At some point she’d stopped ticking off the years.

“Courtney,” she asked. “Is there something wrong with me?”

“No,” I told her. “You’re busy living.”

And so am I. It’s been more than thirty-two years since my own father died. It was on December 19, 1990. But sometimes now, I forget the date.

I told Miss Anita that our focus now is not on the drama and trauma of what happened. Our focus is on carrying out our journey, and so certain moments will recede into the shadows while other experiences come to the fore.

I know it’s hard to imagine there will be a time when the death of a parent, or a sibling or a child, doesn’t occupy your every thought and the pain doesn’t pierce your entire being. But gradually, it may no longer be the center of your world. And that’s a good thing.

It’s up to each of us who’ve come through these valleys to teach others that they can make it out as well. And yes, there will be more grief, but with every loss, you can reach back and remember that somehow you were able to keep going. Knowing that can give you the hope you’ll survive again.

You can learn more about The Invisible Ache: Black Men Identifying Their Pain and Reclaiming Their Power by Courtney B. Vance and Dr. Robin L. Smith here.