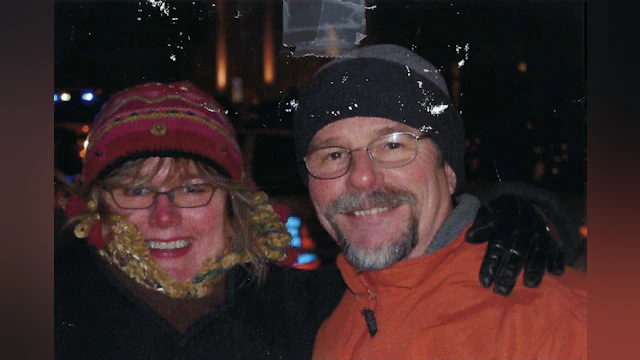

My husband died by suicide two years ago this past January.

After two years, I hear all sorts of well-meaning comments from friends and family. They say I’m “strong,” and, “doing well.” They compliment me on my resilience. In response, I think, “What choice do I have?”

There are also those equally well-meaning people who say things like, “Time to get on Match and start dating!” or, “Why don’t you clean out the closet and make a quilt out of his shirts?” And because my husband died by suicide, I get the comment, “It must be a relief that you don’t have to deal with his depression anymore.” As if that makes his death any less traumatic. As if that makes me miss him any less.

Then there’s the silence that often comes when I mention his name or share a memory. People don’t know how to react, so they don’t say anything at all.

During these last two years, I have learned how to do so much: I make and eat dinner alone; shop for groceries without breaking down; sleep through the night; fix things, and take trips by myself.

I’ve also started to dismantle the parts of his life that he left behind. Yes, his clothes are still in the closet. But I’ve donated his shoes, and removed his name from credit cards, financial institutions, insurance papers, alumni groups, and organizations. I’ve filled plastic bins with his photo albums and scrapbooks, letters, cards, resumes, and yearbooks. I’ve shredded his medical records.

I’ve worked hard during these past two years, and while everyone means well when they comment or give me advice, they may not realize that what may seem like not much progress on the outside, is often huge progress on the inside.

When I joined a spousal grief support group shortly after my husband died, I heard over and over how terrible Year Two would be. “Year One is bad,” the widowed would say, “but Year Two is really rough.” Great, I’d think. That’s just what I want to hear.

This is what I’ve been told: Grief is not linear. Everyone experiences grief differently. Grief moves at its own pace.

That is all true. But there are some commonalities to grieving. During Year One, you’re pretty much in shock, and the numbness created by that shock can help you traverse anniversaries, holidays, and special occasions without completely losing your mind. Even though your heart is breaking, shock helps you put one foot in front of the other to get through your day-to-day existence.

In Year Two, as I transitioned from “we” to “me,” the shock and numbness began to wear off. I asked my therapist how I would know when I was out of shock. She said, “You’ll feel worse.” And that’s true. Now I understand what the widowed in my group meant when they said that Year Two is rough.

Because without the cushion of shock, those anniversaries, holidays, special occasions and daily living hit with a new reality that dope-slapped me in the face and buckled my knees. It’s an everyday reminder that the person I laughed, cried, argued, lived, and loved with is gone.

In grief circles, people talk about grief as a wave. In Year One, those waves come at you like tsunamis. You’re in a constant turmoil of churning water that threatens to pull you under, each and every minute. It’s exhausting just to claw back to the surface and take a breath. Reaching the safety of land seems impossible.

In Year Two, those waves are further apart and not as overwhelming. You get pulled under, but not as deep. There are more hours and days when you are at least treading water, and when the water is calm, you can slowly move toward the land that is now visible on the horizon. Maybe you even find a life jacket.

Year Two, for me, has been full of contradictions. I’m adjusting to my new life even though I miss the past; I feel like I need to make decisions, but then I remind myself that it’s still early on; I try to plan for the future, but I have no idea what that means.

But here’s something interesting: What I also realize in Year Two is that I am pretty much who I was before my husband died. That seems crazy, I know. But although the things we did together are over, and the tenor of those anniversaries, holidays, and special occasions has changed, I’m basically the same person I was before he died. Just because my husband is gone, it doesn’t mean that I’m gone. And that brings me hope.

I am more sad, lonely, tired, and anxious – but I wake up every morning, and the person who looks back at me in the mirror is me. Recognizing who I am each day helps me keep my head above water, and swimming toward that land.

Life can unravel at any time. The last two years upended my life in ways I could never have imagined. So, to know that I’m still me is the hope that I need right now. I get up; I open the blinds; I turn on the radio; I brush my teeth, shower and dress; I feed my cats and dog; I take a walk; and I begin my day.

And no, not every day is a good one. There are plenty of times I’d rather just stay in bed. But I don’t. I get up and try again. Every day. So, if you ask me to describe the difference between Year One and Year Two, I will say it’s one word… hope.

If you’ve lost someone to suicide, you are not alone. AFSP offers information and resources, including our Healing Conversations program.