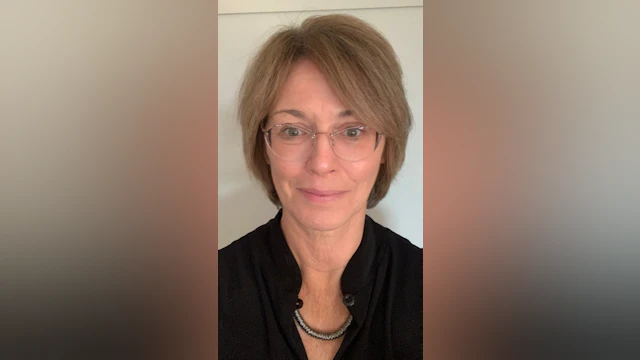

March is Women’s History Month, and I can’t help but think about one of the most important women in my life and in the field of suicide prevention: my mentor Dr. Barbara Stanley. Barbara was a clinical psychologist at Columbia University and the New York State Psychiatric Institute, and one of the world’s foremost leaders in suicide prevention research. I was fortunate to meet her as a recent PhD graduate almost 30 years ago. I cannot overstate how central a figure Barbara has been in my professional life, as mentor, collaborator, role model and friend.

It has been a little over a year since we lost Barbara to cancer in January 2023, yet her enormous impact on the field of suicide prevention and her larger-than-life persona is still very much alive. She spent her work life developing and implementing innovative approaches to suicide first for people with schizophrenia, those with borderline personality disorder, and ultimately for widespread dissemination of suicide prevention strategies. Her impact can be seen across the U.S. and around the world.

She is perhaps best known for the application and development, along with her colleague Dr. Gregory K. Brown, of the Suicide Safety Planning Intervention. Revolutionary in its deceptive simplicity, the Safety Planning Intervention empowered individuals with suicidal ideation and behavior to recognize when their risk may increase, and take steps to implement self-coping strategies that include reaching out for help when necessary. Consisting of a 30-to-45-minute collaborative interaction between a treatment provider and a client, the Safety Planning Intervention generates a six-step plan for how to stay safe during a suicidal crisis. It has been incorporated into behavioral health care settings nationwide, and is considered a best practice for suicide prevention. (Watch Dr. Stanley discuss the Safety Planning Intervention, and read more about it here.)

Barbara was a community builder and used her passion and knowledge to contribute to the study, teaching, and practice of suicide prevention. As a woman, trained as a clinical psychologist in a very male-dominated medical field, she overcame formidable obstacles to obtain millions of dollars in research funding to explore her ideas and to make ground-breaking discoveries to aid in suicide risk detection and prevention intervention. In addition to contributing hundreds of scientific publications and presentations, Barbara took leadership roles, coordinating conferences and serving as President of the International Academy for Suicide Research (IASR), and serving on grant review committees for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH.) Due to her innovative and brilliant scientific thinking and outstanding methodology and ethics, she was highly respected nationally and internationally, and sought after for consultation at every level of inquiry regarding suicide prevention, whether it was to advise on clinical interventions, or influence research directions and policy decisions.

Dr. Stanley believed in a “multi-pronged” approach to suicide prevention. She was a rigorous scientist who was scrupulous in sticking close to the data and in modelling the conduct of ethical research. She brought a unique blend of methodological rigor, creativity and compassion to her approach. She advanced both the scientific and public health fields in research ethics; clinical trials comparing Dialectical Behavior Therapy to other therapy and medication treatments; training therapists; creating models and frameworks for introducing best practices for suicide prevention into clinical settings across New York State, and beyond. She also conducted biological research to identify neurobiological factors that may contribute to an individual’s risk for suicide.

Barbara’s compassion was intimately related to her clinical work in her private practice. Despite her high-powered international career, she was extremely present for and deeply caring of the patients under her care, many of whom were at high risk for suicide. Her scientific inquiries were directly informed by her clinical work and her compassion for her patients — she felt people’s pain and was constantly trying to think of how to better help individuals struggling with suicidal risk, ideation and behaviors. She would go home after a day in her practice and sketch out schematic models based on an insight during a clinical interaction. Through the force of her intellectual brilliance, curiosity, confidence and competence, she was able to turn many of these ideas into viable research projects.

Barbara’s legacy continues through her numerous contributions and her mentoring of numerous young investigators, so many of whom were women. As my mentor, she was extremely generous and provided me with many opportunities, pushing me to achieve professionally, and supporting me in managing my work/life balance as I was starting a family. She, herself, was a proud mother.

I am one of so many who have benefited from her nurturance and guidance along with her creativity and intellect. She inspired us to believe in our ability to do the work. She is sorely missed: a one-of-a-kind individual who cannot be replaced. She inspired and relied on us to believe in ourselves and our ability to keep this important work going. And so, she lives on in our hearts, minds and through the science of suicide prevention. Given her impact, I can’t think of a better way to recognize Women’s History Month than to share Dr. Barbara Stanley’s life and legacy.